Predator Free Welly – the next frontier

This article was originally written by Nikki Macdonald and published by The Post on 1 June 2024. See original article here.

Having conquered Miramar Peninsula, Predator Free Wellington is moving west. investigates what the movement has achieved, and the challenges ahead, including a looming funding hole.

From the summit of Mt Victoria, the capital spills out to the sea. Where most see knobs and flats, the tufty green of Town Belt and asphalt fingers of roads, James Willcocks sees numbers.

‘One’ for easy predator elimination territory – open, hard-edged cityscapes mostly inhospitable to rats. ‘Two’ for lumpy spots with some tricky vegetation. And ‘three’ for classic capital country – steep, weed-bound escarpments that make for slow scrambles for field operators trying to check bait stations and traps.

And then there are the real problem places, points out Willcocks, the project director of Predator Free Wellington.

“We’ve got the zoo in there – so we’re going to have to put people into the lion enclosure to try and get rats out of there. You’ve got the regional hospital, with thousands of vehicle movements every day. We’ve got Government House, with the massive security provisions.”

Ever the optimist, Willcocks calls those challenges opportunities. The source of his optimism lies to the east, beyond the airport runway that acts as a concrete zipper, sealing off Miramar Peninsula. There, they have already made the impossible possible, declaring the promontory rat and stoat free in November 2023.

But the next goal – Predator Free Wellington’s Phase Two – is bigger, and harder. If wrangling a trap and poison network around 20,000 people was tricky, try managing it across 14 suburbs and 70,000 people, stretching from the central business district to the wild south coast.

“Miramar was the first chance to see, can we do this in a peopled landscape,” Willcocks says. “We know how to effect eliminations on offshore islands and in some rural landscapes … Our role is to figure out how we do this in our cities. And that’s our part of the national mission.”

Down the hill at Evans Bay is the predator-killing rolling front line.

The project has secured 10,000 permissions from homeowners to place traps and bait stations. They’ve already cleared the suburbs closest to Miramar – Kilbirnie, Rongotai and Lyall Bay. But Evans Bay is newish, and ratty.

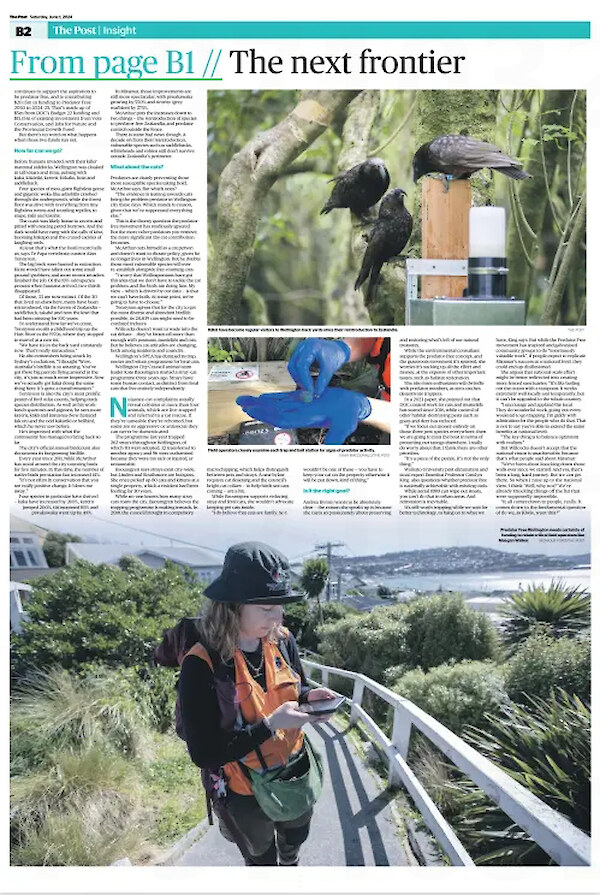

Field operator Meegan Walker checks a bait station halfway up a steep bank. No bait take or nibbles on the chewcard, but a dead rat in the tunnel. Win. She’s one of 23 field operators employed by Predator Free Wellington. They run a surveillance network alongside 10,000 backyard trappers and suburban volunteers.

On a bad day, Walker finds chewcards and bait take at every station. On a good day, the rat sign is replaced by wētā and skinks and flitting pīwakawaka (fantails).

Fellow field operator Jed Prickett spent his morning installing new traps where a colleague suspected network blindspots, and put out chewcards. They were “smashed”, Prickett says.

He’s been working with rats for four years, having come from Wellington trapmaker Goodnature. Some spots just get your rat senses tingling, he says. Scrubby cape ivy is rat heaven. Or a fig-littered backyard or juicy compost bin.

“And dare I say it, you can smell them. Sometimes you walk into an area, and there’s just a whiff … It’s not the sexiest of sciences, but it is the sexiest of outcomes. I was out on Miramar the other day, and just the geckos – almost stepping on them. Checking stations out there is so fun. It’s a treat.”

Prickett opens a bait station and examines the half-eaten blue brodifacoum bait between gloved fingers.

“See those two dots?” he says. “That’s mouse chew.” He fishes out skinny blue poos – size-wise, it could be a mouse or juvenile rat. He replaces the smear of peanut butter lure inside the box and unscrews the neighbouring trap – one of 1489 currently on the Phase Two landscape. The lure has gone but the trap hasn’t triggered – more evidence the culprit is probably a mouse.

This is the level of detective work required for efficient trapping. Every observation is fed back to a live database, used to find pest hotspots and target effort and devices.

“We live and die by the data,” Willcocks says. “When we started we didn’t have any of that.”

It took two years longer than expected (or hoped) to clear Miramar of rats, weasels and stoats. That’s largely because the teams had to write the manual. “We were trying to do everything, everywhere, all at once, and we switched to a rolling front approach.”

Now they have a system. They knock down populations, then go for elimination, and use detector dogs, cameras and chewcards to find the last hotspots.

They also understand so much more about habitat – hence the 1-3 terrain grading system.

All that new knowledge saves money. They’re now spending $2800 per hectare – 75% less than on Miramar. But it still might not be enough.

Money, money, money

So far, Predator Free Wellington (PF Welly) has spent $12 million on research and clearing Miramar of rats and stoats.

That included funding from Crown-owned company Predator Free 2050, established to help achieve the National government’s 2016 vision of a country free of possums, rats, stoats, ferrets and weasels.

While PF Welly also gets money from Next Foundation, and Wellington City Council and Greater Wellington Regional Council have pledged support until 2028, Willcocks still fears for the project’s future.

Predator Free 2050 last year said the looming end of Jobs for Nature and Provincial Growth Fund money meant “securing sustainable future funding is a priority”.

Failure to lock that in would open a $2m hole in PF Welly’s $3.9m annual budget, Willcocks says.

That would risk not only the project’s future, but everything achieved so far.

While Miramar has shown that elimination is possible, it’s also reinforced the counter-argument – that reinvasion is inevitable. Since December, a lone stoat has been caught on camera a dozen times on the peninsula.

And just weeks ago, a resident’s cat caught a rat. Sniffing out its origins, PF Welly’s rat-detecting dog barked up a storm on a freshly delivered pile of firewood. That was a risk no-one had anticipated.

Willcocks says the incidents show the surveillance system works. But it also highlights the need for constant vigilance. And that costs money.

The Covid lockdown also showed how quickly gains can be undone. Willcocks estimates their seven weeks (two rat-breeding seasons) away set the elimination back a year.

“Two rats can have up to eight babies. Do that twice – you run the numbers. We went backwards at a very rapid pace.”

Willcocks admits they need to emphasise the project’s wider benefits, such as reducing rat damage to houses and infrastructure, to justify funding in a cost-of-living crisis.

“Ecologically, the proof is irrefutable, when you see the results on Miramar. Now we know the ecological and social benefits, we really need to tell a strong and compelling economic story.”

A spokesman for Conservation Minister Tama Potaka says the Government continues to support the aspiration to be predator free, and is contributing $20.15m in funding to Predator Free 2050 in 2024-25. That’s made up of $5m from DOC’s Budget 22 funding and $15.15m of existing investment from Vote Conservation, and Jobs for Nature and the Provincial Growth Fund.

But there’s no word on what happens when those two funds run out.

How far can we go?

Before humans invaded, with their killer mammal sidekicks, Wellington was cloaked in tall tōtara and rimu, pulsing with kākā, kākāriki, kererū, kōkako, huia and saddleback.

Four species of moa, giant flightless geese and gigantic weka-like adzebills crashed through the undergrowth, while the forest floor was alive with everything from tiny flightless wrens and scuttling reptiles, to snipe, rails and takahē.

The coast was likely home to ravens and pitted with nesting petrel burrows. And the dark would have rung with the calls of kiwi, booming kākāpō and the crazed cackles of laughing owls.

At least that’s what the fossil record tells us, says Te Papa vertebrate curator Alan Tennyson.

The big birds were hunted to extinction. Kiore would have taken out some small ground-grubbers, and more recent invaders finished the job. Of the 100-odd species present when humans arrived, two-thirds disappeared.

Of those, 33 are now extinct. Of the 30 that lived on elsewhere, many have been reintroduced, via the haven of Zealandia – saddleback, takahē and now the kiwi that had been missing for 100 years.

To understand how far we’ve come, Tennyson recalls a childhood trip up the Hutt River in the 1970s, where they stopped to marvel at a rare tūī.

“We have tūī in the back yard constantly now. That’s really miraculous.”

He also remembers being struck by Sydney’s cockatoos. “I thought ‘Wow, Australia’s birdlife is so amazing. You’ve got these big parrots flying around in the city, it’s just so much more impressive. Now we’ve actually got kākā doing the same thing here. It’s quite a transformation.”

Tennyson is also the city’s most prolific poster of Bird Atlas counts, helping track species distribution. As well as his worklunch sparrows and pigeons, he sees more kererū, kākā and kārearea (New Zealand falcon) and the odd kākāriki or bellbird, which he never saw before.

He’s impressed with what the community has managed to bring back so far.

The city’s official annual birdcount also documents its burgeoning birdlife.

Every year since 2011, Nikki McArthur has stood around the city counting birds for five minutes. In that time, the number of native birds per station has increased 41%.

“It’s not often in conservation that you see really positive change. It blows me away.”

Four species in particular have thrived – kākā have increased by 260%, kererū jumped 200%, tūī increased 85% and pīwakawaka went up by 49%.

In Miramar, those improvements are still more spectacular, with pīwakawaka growing by 550% and riroriro (grey warblers) by 275%.

McArthur puts the increases down to two things – the reintroduction of species to predator-free Zealandia, and predator control outside the fence.

There is some bad news though. A decade on from their reintroduction, vulnerable species such as saddlebacks, whiteheads and robins still don’t survive outside Zealandia’s perimeter.

What about the cats?

Predators are clearly preventing those more susceptible species taking hold, McArthur says. But which ones?

“The evidence is leaning towards cats being the problem predator in Wellington city these days. Which stands to reason, given that we’ve suppressed everything else.”

This is the thorny question the predator free movement has studiously ignored. But the more other predators you remove, the more significant the cat contribution becomes.

McArthur outs himself as a cat person and doesn’t want to dictate policy, given he no longer lives in Wellington. But he doubts those most vulnerable species will ever re-establish alongside free-roaming cats.

“I worry that Wellingtonians have got this idea that we don’t have to tackle the cat problem, and the birds are doing fine. My view – which is driven by our data – is that we can’t have both. At some point, we’re going to have to choose.”

Tennyson agrees that for the city to get the most diverse and abundant birdlife possible, its 28,839 cats might need to be confined indoors.

Willcocks doesn’t want to wade into the cat debate – they’ve bitten off more than enough with possums, mustelids and rats. But he believes cat attitudes are changing, both among residents and councils.

Wellington’s SPCA has dumped its trap, neuter and return programme for feral cats.

Wellington City Council animal team leader Kate Baoumgren started a stray-cat programme three years ago. Strays have some human contact, as distinct from feral cats that live entirely independently.

Nuisance-cat complaints usually reveal colonies of more than four animals, which are live-trapped and referred to a cat rescue. If they’re tameable they’re rehomed, but some are so aggressive or antisocial they can never be domesticated.

The programme last year trapped 262 strays throughout Wellington, of which 113 were adopted, 32 transferred to another agency and 96 were euthanised because they were too sick or injured, or untameable.

Baoumgren says strays exist city-wide, but Linden and Strathmore are hotspots. She once picked up 80 cats and kittens at a single property, which a resident had been feeding for 30 years.

While no-one knows how many stray cats roam the city, Baoumgren believes the trapping programme is making inroads. In 2018, the council brought in compulsory microchipping, which helps distinguish between pets and strays. A new bylaw requires cat desexing and the council’s bright cat collars – to help birds see cats coming – are a hit.

While Baoumgren supports reducing stray and feral cats, she wouldn’t advocate keeping pet cats inside.

“I do believe that cats are family. So I wouldn’t be one of these – you have to keep your cat on the property otherwise it will be put down, kind of thing.”

Is it the right goal?

Andrea Byrom wants to be absolutely clear – the reason she speaks up is because she cares so passionately about preserving and restoring what’s left of our natural treasures.

While the environmental consultant supports the predator-free concept, and the grassroots movement it’s spurred, she worries it’s sucking up all the effort and money, at the expense of other important issues, such as habitat restoration.

She also fears enthusiasm will dwindle with predator numbers, as zero catches demotivate trappers.

In a 2023 paper, she pointed out that DOC control work for rats and mustelids has soared since 2016, while control of other habitat-destroying pests such as goats and deer has reduced.

“If we focus our money entirely on those three pest species everywhere, then we are going to miss the boat in terms of protecting our taonga elsewhere. I really do worry about that. I think there are other priorities.

“It’s a piece of the puzzle. It’s not the only thing.”

Waikato University pest elimination and stoat expert Emeritus Professor Carolyn King also questions whether predator free is nationally achievable with existing tools.

While aerial 1080 can wipe out stoats, you can’t do that in urban areas. And reinvasion is inevitable.

It’s still worth trapping while we wait for better technology, to hang on to what we have, King says. But while the Predator Free movement has inspired and galvanised community groups to do “enormously valuable work”, if people expect to replicate Miramar’s success at a national level, they could end up disillusioned.

She argues that national-scale effort might be better redirected into creating more fenced sanctuaries. “It’s like bailing out the ocean with a teaspoon. It works extremely well locally and temporarily, but it can’t be upgraded to the whole country.

“I encourage and applaud the local. They do wonderful work, going out every weekend to go trapping. I’m giddy with admiration for the people who do that. That is not to say you’re able to extend the same benefits at national level.

“The key thing is to balance optimism with realism.”

But Willcocks doesn’t accept that the national vision is unachievable, because that’s what people said about Miramar.

“We’ve been about knocking down those walls ever since we started. And yes, that’s been a long, hard journey. But we can get there. So when I raise up to the national view, I think ‘Well, why not?’ We’re already knocking things off the list that were supposedly impossible.

“It all comes down to people, really. It comes down to the fundamental question of do we, as Kiwis, want this?’’

Posted: 2 June 2024