Making biosecurity smarter, not just bigger

This case study was first published in our 2024/25 impact report

The challenge

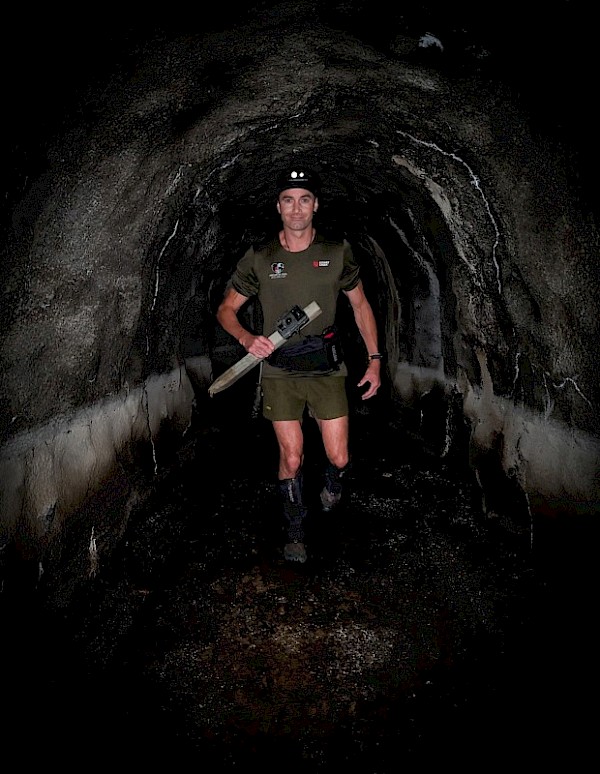

Tim installing a rat-detection camera in a tunnel in Miramar. Complex urban landscapes like these make predator elimination challenging and innovative. Photo – Tim SuttonHow lean can we make biosecurity monitoring while still catching rats early?

Tim installing a rat-detection camera in a tunnel in Miramar. Complex urban landscapes like these make predator elimination challenging and innovative. Photo – Tim SuttonHow lean can we make biosecurity monitoring while still catching rats early?

This past year, we faced competing pressures: we needed to protect the gains in Miramar while maximising our time and budget for advancing into Phase 2. We also needed rapid, accurate detection methods that could cover ground quickly when rat activity was sparse. A rat incursion in Maupuia gave us an unexpected – and costly – answer about what doesn’t work, pushing us to innovate across our entire biosecurity approach.

Think of it like the Swiss cheese model: each detection method has holes (gaps in coverage, times when it misses things). If you only use one method, or space devices too far apart, the holes line up and rats slip through undetected. We could theoretically put devices everywhere and eliminate all gaps – but that’s not financially sustainable. The challenge was closing enough holes to catch rats early, using the minimum number of devices and methods that still worked. Smart coverage, not total coverage.

We tested this the hard way.

What happened

In the past 12 months, we deliberately thinned our Miramar biosecurity network to see if we could make it cheaper and faster to maintain. Trail cameras were reduced from one per hectare to one per 5 hectares (or less), checked every 4-5 weeks instead of monthly. The goal: free up resources for Phase 2 clearance work while still protecting Miramar.

In May 2025, a public sighting tipped us off to rat activity in Maupuia. We responded immediately with dog detection, traps, bait stations, chew cards, and additional cameras. What we found wasn’t encouraging: ship rats had already invaded, bred, and spread across approximately 40 hectares. It took three months of intensive work to eliminate them – 39 rats in total.

The network had been too sparse for the high-risk urban areas. We’d found the wrong side of the efficiency line.

Our approach

The Maupuia event clarified what we needed: not just more devices, but smarter deployment using multiple complementary detection methods, each with different strengths and costs:

- Cameras: Varying density based on risk (expensive, but excellent for confirmation and long-term monitoring – mayonnaise lures lasts months vs chew cards that mice can consume in days)

- Chew cards: One per hectare in key areas (cheap, can deploy densely)

- Dog surveys: Mobile detection covering ground quickly (periodic, highly effective – especially when rat activity is sparse)

- Community reporting: Eyes everywhere (free!)

Strategic placement using historical data:

Rather than simply spacing devices evenly across the landscape, we now use heat mapping of historical rat activity to inform where we place our monitoring devices. This data-driven approach means cameras and chew cards go where rats are most likely to appear – near boundaries, along movement corridors, and in areas with previous detections. When you have fewer cameras, placement becomes absolutely critical. A poorly placed camera means missing a population until it spreads to the next device, 5 or more hectares away.

The results were immediate. Our optimised cameras spotted rats five times in places where we had previously never seen rats across three years of monitoring.

Innovating Dog Detection:

We’ve systematised how we use our detection dog team to maximise efficiency. We created biosecurity check areas with inspection rotations – monthly, quarterly, or half-yealy – based on habitat quality and historic rat data. These rotations adapt as activity patterns change. Within each area, specific points are chosen based on historical detections and suitable rat habitat, making detection more targeted and effective.

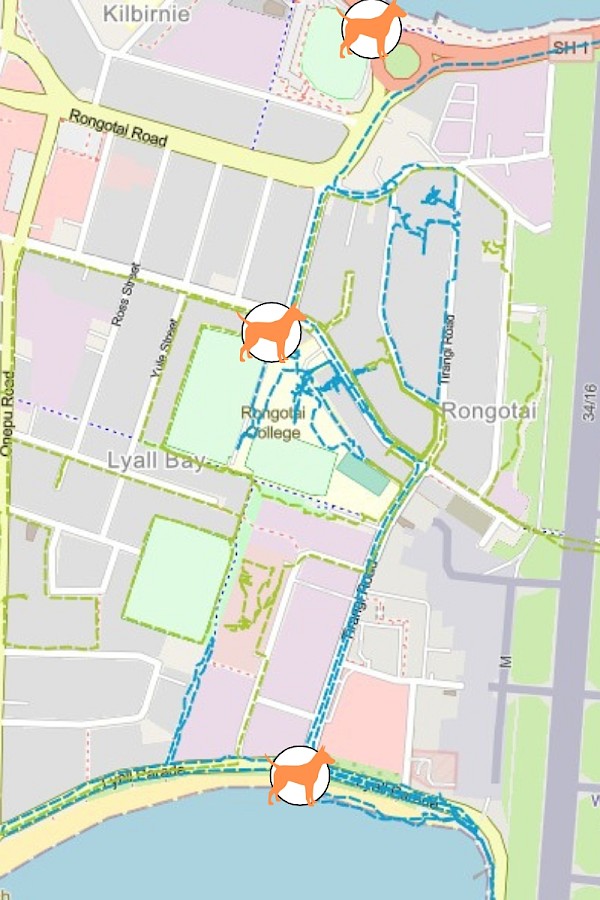

A map of dog detections of rats in Rongotai (click to expand). The blue lines are Sally’s GPS tracks with the dogs. Orange icons are passive dog detections, where there may have been old activity.We’ve also automated dog detection data and dog line tracking in our field map system. The field team can now view this information in real time, and data flows automatically to and from the field and office without manual data entry. This has eliminated daily manual data imports and extraction tasks for our Eradication Technical Officers (ETOs), saving significant time while improving accuracy.

A map of dog detections of rats in Rongotai (click to expand). The blue lines are Sally’s GPS tracks with the dogs. Orange icons are passive dog detections, where there may have been old activity.We’ve also automated dog detection data and dog line tracking in our field map system. The field team can now view this information in real time, and data flows automatically to and from the field and office without manual data entry. This has eliminated daily manual data imports and extraction tasks for our Eradication Technical Officers (ETOs), saving significant time while improving accuracy.

We then matched monitoring intensity to risk level:

- Monitoring phase (just cleared): Check everything every 3 weeks – cameras, chew cards, any previously active devices. Dog surveys as needed for rapid ground coverage.

- High-risk phase (3 months detection-free): Monthly checks of cameras and chew cards. Cameras are deployed at 1 per 1.6 hectares, and chew cards will be placed at interim sites so that, together, we reach 1 monitoring device per hectare. Dog surveys every 1-3 months. High-risk areas include recent clearances (possible survivors), excellent rat habitat, and urban edges with increased incursion risk.

- Moderate-risk phase (1 year detection-free): Monthly checks of cameras and chew cards. Cameras are deployed at 1 per 6.2 hectares, and chew cards will be placed at interim sites so that, together, we reach 1 monitoring device per 5 hectares. Dog surveys every 3-6 months.

- Low-risk phase (historically quiet areas): Chew cards will be placed based on the historic rat activities and achieve the density of 1 per 10 hectares. Community reporting and dog surveys every 6 months.

Efficiency gains:

- Routes planned so one site visit checks multiple devices along the same path

- 5x better coverage density (chew cards at 1/hectare vs cameras at 1/5 hectares) achieved without 5x cost increase

- Resources concentrated where risk is highest based on historical activity patterns

- Strategic camera placement using heat maps ensures devices are positioned where they’re most likely to detect activity

- Automated dog detection data eliminates daily manual data processing

- Systematic dog detection schedules maximise Sally’s effectiveness while minimising redundant coverage

What’s next

We’re rolling this refined system out across all cleared areas and training volunteer specialists to run biosecurity monitoring in their zones. This shifts us from elimination mode to biosecurity mode – and proves the model can sustain itself.

For dog detection specifically: We’re conducting statistical analyses on Sally’s detections to evaluate the accuracy of different detection types (active, passive, tracking). Based on these results, we’ll finalise response protocols that vary depending on the detection type – ensuring we respond appropriately to different levels of detection certainty.

The Maupuia incursion was initially disappointing for our team, but it gave us invaluable data. We now know where the line is between too sparse (risky) and appropriate coverage (efficient and effective). That knowledge feeds into the collective learning toward Predator Free 2050.

Why this matters

- For Wellington: This system makes our exit strategy possible. We can confidently hand cleared areas to volunteer biosecurity teams knowing the monitoring framework actually works – and we learnt what ‘actually works’ means through real-world testing and continuous innovation.

- For urban conservation: Most projects fail because they can’t afford to defend gains forever. We’re creating and refining the first model of what predator free biosecurity looks like in an urban area. We know incursion events will continue, but we’re using each one to learn and improve. This shows how to build cost-effective, sustainable biosecurity that doesn’t require permanent paid staff in every cleared area. The framework is replicable, and other predator free projects can draw on our experience to improve their outcomes.

Posted: 10 February 2026